Domestic Abuse Practice Guidance

Purpose of the Domestic Abuse Practice Guidance

This practice guidance is written to assist all staff working with unborn babies (UBB), children and young people to recognise and respond appropriately to situations of Domestic Abuse. For the purpose of this document, we will use the word children or child to denote a person under the age of 18 years.

Domestic abuse can affect anyone, regardless of age, disability, gender identity, gender reassignment, race, religion or belief, sex or sexual orientation. Domestic abuse can also manifest itself in specific ways within different communities. Women are disproportionately the victims of domestic abuse. The Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) for the year ending March 2020, estimated that 1.6 million females and 757, 000 males aged 16-74 years had experienced domestic abuse in that year.

Research consistently shows that pregnancy can be a trigger for domestic abuse, and existing abuse may get worse during pregnancy of after giving birth.

Over 40% of victims of partner abuse have at least one child under the age of 16 years old living in the housing.

In The year ending December 2021 there were 11,589 Incidents and crimes relating to Domestic Abuse across North Yorkshire.

Definition of Domestic Abuse

The Domestic Abuse Act 2021 defines Domestic Abuse

PART 1

Definition of “domestic abuse”

This section defines “domestic abuse” for the purposes of this Act.

Behaviour of a person (“A”) towards another person (“B”) is “domestic abuse” if—

(a) A and B are each aged 16 or over and are personally connected to each other, and

(b) The behaviour is abusive.

Behaviour is “abusive” if it consists of any of the following—

(a) Physical or sexual abuse;

(b) Violent or threatening behaviour;

(c) Controlling or coercive behaviour;

(d) Economic abuse (see subsection (4));

(e) Psychological, emotional or other abuse;

and it does not matter whether the behaviour consists of a single incident or a course of conduct.

“Economic abuse” means any behaviour that has a substantial adverse effect on B’s ability to—

(a) Acquire, use or maintain money or other property, or

(b) Obtain goods or services.

For the purposes of this Act A’s behaviour may be behaviour “towards” B despite the fact that it consists of conduct directed at another person (for example, B’s child).

References in this Act to being abusive towards another person are to be read in accordance with this section.

For the meaning of “personally connected”, see section 2.

2. Definition of “personally connected”

For the purposes of this Act, two people are “personally connected” to each other if any of the following applies—

(a) They are, or have been, married to each other;

(b) They are, or have been, civil partners of each other;

(c) They have agreed to marry one another (whether or not the agreement has been terminated);

(d) They have entered into a civil partnership agreement (whether or not the agreement has been terminated);

(e) They are, or have been, in an intimate personal relationship with each other;

(f) They each have, or there has been a time when they each have had, a parental relationship in relation to the same child (see subsection (2));

(g) They are relatives.

For the purposes of subsection (1)(f) a person has a parental relationship in relation to a child if—

(a) The person is a parent of the child, or

(b) The person has parental responsibility for the child.

(3) In this section—

- “child” means a person under the age of 18 years;

- “civil partnership agreement” has the meaning given by section 73 of the Civil Partnership Act 2004;

- “parental responsibility” has the same meaning as in the Children Act 1989 (see section 3 of that Act);

- “relative” has the meaning given by section 63(1) of the Family Law Act 1996.

Other forms of abuse may be present for example:

Abuse by family members which can involve abuse by any relative or multiple relatives. Abuse within a family set-up can encompass a number of different behaviours, including but not limited to violence, coercive or controlling behaviours, and economic abuse. Abuse by family members also encompasses forced marriage, so called ‘honour’-based abuse and female genital mutilation.

Technological abuse using technology and social media as a means of controlling or coercing victims. This happens frequently both during and after relationships with abusers and is particularly common amongst younger people.

Spiritual abuse using religion and faith systems to control and subjugate a victim often characterised by a systemic pattern of coercive or controlling behaviour within a religious context. A form of spiritual abuse may include the withholding of a religious divorce, as a threat to control and intimidate victims.

Indicators of Domestic Abuse

Professionals should be alert to the signs that a child or adult may be experiencing domestic abuse, or that a partner may be perpetrating domestic abuse. Professionals should always consider during an assessment the need to offer children and adults the opportunity of being seen alone and ask whether they are experiencing, or have previously experienced, domestic abuse.

Professionals who are in contact with adults who are threatening or abusive to them need to be alert to the potential that these individuals may be abusive in their personal relationships and assess whether domestic abuse is occurring within the family.

There are a number of factors which may indicate the potential risk of harm to victims and children when domestic abuse is present in a family, these factors may include:

- Escalation in frequency and severity of violence and abuse;

- Previous incidents of physical violence including injuries to the victim;

- Perpetrator has a history of domestic abuse with previous partners and may also have a previous history of offending including breach of civil or criminal court order or bail conditions by the suspect;

- Controlling, jealous, obsessive behaviours by the perpetrator especially stalking;

- Having (particularly pre-school) children, especially if from a previous relationship;

- Mental health issues for the victim or perpetrator especially where the perpetrator has threatened suicide;

- Victim and/or child verbalizing their fear of the perpetrator;

- The victim is pregnant or has recently given birth or has a long-term illness, a disability, or a mental health problem;

- The perpetrator has access to or has used or threatened to use weapons or there have been incidents of non-fatal strangulation;

- Children present as withdrawn within the household;

- Where illicit drug use, mental ill-health, and problematic alcohol use are present they will increase the risk;

- Current or imminent separation from the suspect and child disputes especially over contact or finances;

- Insecure immigration status and no recourse to public funds are significant barriers to safety for adult and child victims of domestic abuse.

Protective factors in some of these circumstances may be limited and the children may have suffered, or be likely to suffer, Significant Harm. Professionals should make a record of their assessment and the information that underpins it, inform their line manager and refer to Children’s Social Care.

Statistically the period following separation is the most dangerous time for serious injury and death. Professionals in contact with children and their families in these cases would also need to consider:

- The previous level of physical danger to the adult victim and in particular the presence of the child during violent episodes;

- The previous pattern of power, control and intimidation in addition to the physical violence;

- Any threats to hurt or kill family members or abduct the children;

- Any reported stalking or obsession about the separated partner or the family;

- Any issues relating to contact – is it a desire to promote the child’s best interest or as a means of continuing intimidation, harassment or violence to the other parent; what are the children’s views about contact?

- The attitude of the parent to their past violence and capacity to appreciate its effect, and whether they are motivated and have the capacity to change;

- Be alert to cultural issues when dealing with ethnic minority victims and that, in leaving a partner, they may be ostracised by family, friends and the wider community increasing the risks to their safety.

In situations when the adult victim has left the perpetrator taking the children, professionals need to be alert to the on-going potential for risk. The dynamics of domestic abuse are based on the perpetrator maintaining power and control over their partner. Challenges to that power and control, for example, by separation may increase the likelihood of escalating abuse.

Children as victims of domestic abuse

(1)This section applies where behaviour of a person (“A”) towards another person (“B”) is domestic abuse.

(2) Any reference in this Act to a victim of domestic abuse includes a reference to a child who—

(a) Sees or hears, or experiences the effects of, the abuse, and

(b) Is related to A or B.

(3) A child is related to a person for the purposes of subsection (2) if—

(a) The person is a parent of, or has parental responsibility for, the child, or

(b) The child and the person are relatives.

(4)In this section—

- “child” means a person under the age of 18 years;

- “parental responsibility” has the same meaning as in the Children Act 1989 (see section 3 of that Act);

- “relative” has the meaning given by section 63(1) of the Family Law Act 1996.

It is noted that, although a child does not have any rights in law until he or she is born, research shows that unborn babies can also be affected by domestic violence whilst in utero.

Domestic Abuse Data :

Domestic abuse:

- Will affect 1 in 4 women, and 1 in 6 men, during their lifetime;

- Leads to, on average, two women being murdered each week, and 30 men per year;

- Accounts for 16% of all violent crime, however it is still the violent crime least likely to be reported to the police;

- Has more repeat victims than any other crime (average on there will have been 35 domestic abuse assaults before a victim calls the police) and women will approach 9 different agencies for help before effective help is offered; and

- The single most quoted reason for becoming homeless.

Data in relation to children, taken from Getting it Right First Time by Safe Lives found that:

- a quarter of the children living with high risk domestic abuse are under 3 years old, and

- 62% of children are directly harmed

Additionally we know that in the majority of Serious Case Reviews (i.e. a review of multi-agency working where a child has died, or been seriously harmed, and abuse or neglect are believed to be a factor) domestic abuse is an issue within that household.

Situational couple violence (SCV) (Situationally-provoked violence)

- Violence that occurs because the couple has conflict which turns into arguments that can escalate into emotional and possibly physical violence.

- SCV often involves both partners.

- Women are as likely as men to engage in SCV but the impact on women (when committed by men), is much larger (due to physical size etc.). This can be in terms of physical injury, as well as fear and psychological consequences. In about a quarter of cases it is only the man who is violent; in about a quarter of cases it is only the woman who is violent, and in the other half of cases both the man and the woman have been violent at some point in the relationship.

- Violence can on occasions escalate to become chronic and severe.

- SCV follows a socio-economic gradient and is more prevalent in poorer families. Substance misuse, anger management issues and communication issues are deeply implicated. SCV is more common than intimate terrorism in co-habiting relationships than in marriages.

- Alcohol plays a significant role in SCV as a source of conflict in itself and as a factor which leads to escalation of violence.

- In 40% of couples characterised by this type of violence, the SCV comprises one incident (such as a slap, or a push). The couple is horrified by what has happened, deals with it, and there is no further violence within the relationship. For the remainder, there is chronic violence (ranging from a few incidents per year to chronic arguing that frequently turns to violence).[1]

What are the factors?

Isolation

Isolation of an individual in an abusive relationship is an emotional and psychologically harmful and distressing time. Isolation occurs when the abusive partner creates a dependency on himself or herself, for example preventing the abused partner from seeing friends and family by making threats about harming themselves, children, pets etc. We know nationally that through the COVID 19 Pandemic calls from victims of domestic abuse have escalated significantly and the need for safe space and outlets for disclosure have evolved in many different localities including testing sites, GP surgeries and pharmacies.

Preventing the abused partner from communication with anyone apart from the abuser themselves means the abused partner becomes solely reliant on them for everything and as a result, this creates fear and further isolation for the victim.

Identifying Isolation

Isolation can be hard to identify, however clear indicators can be seen e.g. when the suspected abused partner is looking to their partner for approval before they speak or answer questions, or when the abused partner is never seen by professionals without the abusing partner being present, or when the abusing partner prevents family or friends support. The abused individual is also likely to be withdrawn depending on the reasons the abusive partner may have offered as to why they only have each other. For example if the abusive partner has told the other partner that no one likes them, severe self-doubt and low self-esteem may have been created.

Significant changes in weight and physical appearance may also be visible in the abused individual, although this is not always the case.

Stalking and Harassment?

What is Stalking and Harassment?

Stalking is a pattern of repeated (two or more occasions) and unwanted behaviour that may cause an individual to feel distressed, scared or intimidated. Both males and females can commit this offence. Stalking can happen with or without a fear of physical violence. This means if an individual is receiving unwanted contact (in person, by letter, email or phone), but the person has never threatened the individual, this is still stalking and is not acceptable.

Stalking can, and often does have a huge emotional impact on those it affects. It can lead to feelings of depression, anxiety and even post-traumatic stress disorder. It is a psychological as well as a physical crime. What can make the problem particularly hard to cope with is that it can go on over a long period of time, making victims constantly anxious and afraid. Sometimes the problem can build up slowly and it can take a while for the victim to realise that they are caught up in an on-going campaign of abuse. The problem isn’t always ‘physical’ because of the internet and phone access, and ‘cyber-stalking’ or online threats or repeated unwanted phone calls can be just as intimidating for the victim.

- Stalking is one of the most common types of intimate violence

- The most common perpetrator in incidents of stalking is a partner or ex-partner

- 18.1% of women aged 16-59 and 9.4% of men aged 16-59 say they have experienced stalking since the age of 16.

There are many forms of harassment ranging from unwanted attention from somebody seeking a romantic relationship to violent predatory behaviour.

Types of stalker

- The rejected – who pursue ex-partners, in the hope of reconciliation, for vengeance or both.

- Intimacy seekers – who stalk someone they believe that they love and who they think will reciprocate.

- Incompetent suitors – who inappropriately intrude on someone, usually seeking a date or brief sexual encounter.

- The resentful – who pursue victims to take out revenge.

- The predatory – whose stalking forms part of sexual offending.

It is of note that professionals working with children can also experience ‘resentful’ stalking following a child being referred to Children’s Social Care, becoming subject to a Child Protection Plan, becoming Looked After, or following information being shared with another agency, e.g. Police, Children’s Social Care. In such cases, the professional’s Human Resources department & the Police must always be informed.

The Law:

Everyone has the right to go about their daily business in safety and without fear. The constant worry of being stalked can affect physical & emotional health. Harassment and stalking are offences. As of 25th November 2012 amendments to the Protection from Harassment Act were made which established stalking as a specific offence in England and Wales.

There are two amendments –

- Section 2A stalking and Section 4A stalking: To prove a section 2A it needs to be shown that a perpetrator pursued a course of conduct which amounts to harassment and that the particular harassment can be described as stalking behaviour. A ‘course of conduct’ is two or more incidents.

- Section 4A is stalking involving fear of violence or serious alarm or distress: Serious alarm and distress is not defined but can include behaviour which causes the victim to suffer emotional or psychological trauma or have to change the way they live their life.

If you are concerned a person may be a victim of stalking or harassment then you should contact the Police on 101 for non-emergencies or 999 in an emergency, i.e. where there is an immediate threat or danger to someone.

Honour Based Violence (HBV)

HBV is a crime or incident, which has or may have been committed, to ‘protect or defend the honour of the family and/or community’. HBV has the potential to be both a domestic abuse incident and a child abuse incident or concern. HBV is sometimes referred to as ”Izzat” which means dignity, honour, reputation, or social rank.

Individuals, families and even communities may take drastic steps to preserve, protect or avenge their ‘honour’; this can lead to a substantial breach of human rights and can include the following abuse:

- All forms of domestic abuse

- Assaults

- Disfigurement

- Versions of sati (burning)

- Sexual assault and rape

- Forced Marriage

Attitudes, behaviour and actions that may constitute ‘dishonour’ are wide ranging and can include:

- Reporting domestic abuse to a third person

- Smoking

- ‘Inappropriate’ make up or dress

- Running away from home

- ‘Allowing’ rape

- Having a boyfriend

- Pregnancy outside marriage

- Interfaith relationships

- Rejecting a forced or arranged marriage

- Leaving a spouse

- Requesting a divorce

- Intimacy in a public place

- Declaring being gay or lesbian

DO NOT UNDERESTIMATE THE FACT THAT PERPETRATORS OF HBV REALLY DO AND WILL KILL THEIR CLOSEST RELATIVES AND/OR OTHERS FOR WHAT MAY APPEAR TO BE A MINOR OR TRIVIAL TRANSGRESSION.

Consider the family and the information you have to share; is it possible you could be putting someone in the family at risk of HBV? If so you should seek further guidance from your manager regarding next steps to safeguard the person.

Forced Marriage

A forced marriage is where one, or both people do not (or in cases of people with learning disabilities, cannot), consent to the marriage and pressure or abuse is used. It is recognised in the UK as a form of abuse against women and men, domestic/child abuse and a serious abuse of human rights. A marriage must be entered into with free will and consent. The pressure put on people to marry against their will can be physical or sexual, including threats, emotional, psychological or financial.

NB: Forced Marriage is NOT the same as arranged marriage, which is one where parents or elders may identify a ‘suitable’ marriage partner, but where the prospective spouses may choose whether or not they wish to accept the partnership and no pressure is brought on this decision.

Key Motivations of a Forced Marriage:

- Controlling unwanted behaviour and sexuality (including perceived promiscuity, gay, lesbian, bisexual or transsexual), in particular the behaviour and sexuality of women.

- Protecting “family honour”.

- Peer group and family pressure.

- Attempting to strengthen family links.

- Ensuring land, property and wealth remains within the family.

- Protecting perceived cultural ideals.

- Protecting perceived religious ideals, which maybe misguided.

- Preventing “unsuitable” relationships, e.g. those outside ethnic, cultural, religious or caste group.

- Assisting claims for residence and citizenship.

- Fulfilling long-standing family commitments.

Adolescent to Parent Violence

Child on parent abuse is often referred to as adolescent to parent abuse. Whilst the definition of domestic abuse applies to those aged 16 or over, is it recognised that child on parent abuse does occur and needs to be addressed, and can be perpetrated by those under 16 years old.

There is currently no legal definition of child on parent abuse. However, it is increasingly recognised as a form of domestic abuse and, depending on the age of the child, it may fall under the government’s official definition of domestic violence and abuse.

It is more likely to involve a pattern of behaviour. This can include physical violence from an adolescent towards a parent and/or a number of different types of abusive behaviours, including

- damage to property,

- emotional abuse,

- economic/financial abuse

- sexual abuse

- coercive control

Violence and abuse can occur together or separately. Abusive behaviours can encompass, but are not limited to:

- humiliating language and threats,

- belittling a parent,

- damage to property

- stealing from a parent, and,

- Heightened sexualised behaviours.

Patterns of coercive control are often seen in cases of child on parent abuse, but some families might experience episodes of explosive physical violence from their adolescent with fewer controlling, abusive behaviours. Although practitioners may be required to respond to a single incident of abuse, it is important to gain an understanding of the pattern of behaviour behind an incident and the history of the relationship between the young person and the parent.

It is also important to understand the pattern of behaviour in the family unit; siblings may also be abused or be abusive. There may also be a history of domestic abuse, or current domestic abuse occurring between the parents/carers of the young person. It is important to recognise the effects child to parent’s abuse may have on both the parent/carer and the young person and to establish trust and support for both.

A report in January 2014 by BBC newsbeat raised the growing issue of parents being abused by their children. A group called Family Lives stated that a third of recent calls to its helpline had been regarding children being physically aggressive.

A Home Office minister recognised it as “a serious and often hidden issue”.

The advice from the charity Young Minds is to firstly try and understand why the young person might be feeling so angry, and acknowledge the issue whilst putting strong boundaries in place of what behaviour is and isn’t acceptable. If the situation continues or gets worse a local GP could be a good starting point for referral to services such as the IDAS Respect Programme where there is clear evidence of child to parent abuse, or abusive behaviour by a child to any member of their family.

IDAS can also offer support to young ‘abusers’ and their parents/carers through the RESPECT Young People’s Programme. The Programme is available to any young people aged between 10 and 16 years who are who are demonstrating abusive behaviour within the family setting; this can be directed towards parents, carers, siblings and other family members.

To make a referral to the IDAS Respect programme complete the referral form below and send it to respect@idas.org.uk

IDAS Respect Programme Referral Form

Further information on Child to Parent Violence and abuse can be found in the One Minute Guide: NYSCP (safeguardingchildren.co.uk)

How Domestic Abuse impacts on Children

Impact on Children

Children who witness domestic abuse suffer emotional and psychological abuse. They tend to have low self-esteem and experience increased levels of anxiety, depression, anger and fear, aggressive and violent behaviours, including bullying, lack of conflict resolution skills, lack of empathy for others, poor peer relationships, poor school performance, anti-social behaviour, pregnancy, alcohol and substance misuse, self-blame, hopelessness, shame and apathy, post-traumatic stress disorder – symptoms such as hyper-vigilance, nightmares and intrusive thoughts – images of violence & abuse, insomnia, enuresis (bed wetting) and over protectiveness of the victim and/or siblings.

The impact of domestic abuse on children is similar to the effects of any other abuse or trauma and will depend upon such factors as:

- The severity and nature of the domestic abuse;

- The length of time the child is exposed to the domestic abuse;

- Characteristics of the child’s gender, ethnic origin, age, disability, socio economic and cultural background;

- The warmth and support the child receives in their relationship with their abused and abusive parents/carers, siblings and other family members;

- The nature and length of the child’s wider relationships and social networks; and

- The child’s capacity for and actual level of self-protection.

For unborn babies, research shows that an unborn baby can be affected by the stressors of their environment. A woman releases hormones into her body in response to the threat of abuse and this can permeate into the placenta affecting the unborn baby, in particular, their neurological development. Unborn babies can also die when their mother is being physically and sexually assaulted in pregnancy.

Factors which increased vulnerability / risk and appropriate interventions

- Unborn babies are particularly vulnerable due to the abuse of their mother. Pregnant women are at increased risk of miscarriage, infection, and premature birth, and the baby is vulnerable to low birth weight, foetal injury and foetal death. Pregnancy can increase the likelihood of domestic abuse, or increase the frequency and severity of domestic violence. Therefore a pregnant women is more vulnerable

- Babies under 12 months old are particularly vulnerable to physical abuse. Where there is domestic abuse in families with a child under 12 months old (including an unborn child), even if the child was not present, any single incident of domestic abuse can negatively affect the baby’s well-being.

- If there is a child or a parent who has special needs, the risk of harm to the child, the parent and other children in the family is increased because the child or parent may not have the ability to implement an effective safety strategy without support from professionals.

- If the parent is a vulnerable adult, professionals should follow their local Safeguarding Adults procedures. These can be found by visiting: www.safeguardingadults.co.uk

- Domestic Abuse directed towards a care giver may draw attention away from the fact that a child in the family may be being sexually or physically abused or targeted in some other way.

Professionals should also assure themselves that a child is not perpetrating abuse towards other family members. Or intervening within the domestic abuse thus putting themselves at risk of physical harm and violence

Early-intervention is key to addressing domestic abuse and preventing an escalation and increase in risk. It is not always easy to know what to do when you are concerned about the impact of Domestic Abuse on a child or young person, but following the guidance below will help:

- Where analysis of the information that you are aware of about the domestic abuse gives rise to concerns about a child’s safety and welfare, then a referral should be made to Children and Families Service via the Multi Agency Screening Team (MAST) immediately. Details about how to make a referral can be found https://www.safeguardingchildren.co.uk/about-us/worried-about-a-child/

- Assess the risk according to the NYSCP Threshold Guidance checklist; NYSCP (safeguardingchildren.co.uk). You may also choose to assess risk using the ‘safer lives CAADA-DASH’ form Resources for identifying the risk victims face | Safelives. This form allows you to ask a series of questions to understand the situation more and assess risk for the victim, unborn baby and children.

- Safeguarding guidance stresses that practitioners should be particularly concerned regarding children whose parents or carers are experiencing difficulties in meeting their needs as a result of domestic abuse, substance misuse, mental illness and/or learning disability.

- The IDAS Multi-agency, whole family approach to working with children and young people impacted by domestic abuse has been commissioned by the Office of the Police, Fire and Crime Commissioner as part of coordinated commissioning arrangements with North Yorkshire Council and City of York. Work with children and families is now in place across North Yorkshire with trained staff engaging with individuals to help families cope and recover from trauma.

- If additional concerns are raised that would warrant information and/or intelligence being shared with police, this must be done via the online Community Partnership Intelligence form. This form provides a key and safe way for professionals to share information about something that may be concerning them for example:

- Information about a concerning incident

- Suspicious activity

- An unusual exchange between two or more people

- Something that makes professionals feel uncomfortable.

Further guidance on the sharing of intelligence can be found on the NYSCP website here: NYSCP (safeguardingchildren.co.uk)

More information about impact for children and young people can be found here: Children and young people – IDAS

Meetings

Many abused partners, despite a decision to separate, believe that it is in the children’s interest to see their other parent/ carer. In other circumstances parents may be compelled by the courts to allow time with each or other parent.

Victims of abuse can be most vulnerable to serious violent assault in the period just before and after separation. Time spent with one or other parent can be a mechanism for the abusive partner to locate the other partner and child which can create significant risk for all those present.

Abusive partners may use this opportunity with the child to hurt the other partner, for example, verbally abusing the partner to the child, belittling the other parent or blaming them for the separation. Thus, through meeting the child/ren can be exposed to further physical and/or emotional and psychological harm, and professionals with ongoing engagement with the non-abusing parent or the children of the relationship need to be vigilant regarding this potential issue.

Professionals supporting separation plans should consider at an early point the victim of abuse’s views regarding post-separation meetings. The professional should clearly outline for the partner facing abuse the factors which need to be considered to judge that this liaison is in the child’s best interests.

Professionals should also speak with and listen to each child regarding post-separation meetings.

Where the assessment concludes that there is a risk of harm, the professional must recommend that unsupervised meetings should not occur until a fuller risk assessment has been undertaken by an agency with expertise in working with abusers.

Professionals should advise victims of abuse of their legal rights if an abusive partner makes a private law application for engagement and meetings. This should include the option of asking for a referral to the Children and Family Court Advisory and Support Service (CAFCASS) Safe Contact Project.

If there is an assessment that unsupervised meeting or contact of any kind should not occur, professionals should ensure that this opinion is brought to the attention of any court hearing applications for contact. Professionals should ensure that any supervised meeting is safe for the parent/carer and the child, and reviewed regularly. The child’s views should be sought as part of this review process.

Domestic Abuse in Young People’s Relationships

Young women in the 16 to 24 age group are most at risk of being victims of domestic abuse. Whilst they are under the age of 18 years, these young women (in some cases teenage mothers) should receive support and safeguarding in line with the Children Act 1989 and Children Act 2004.

For young women aged 18 to 24 years, professionals should follow their local Safeguarding Adults procedure.

Professionals who come into contact with young people should be aware of the possibility that the young person could be experiencing violence within their relationship.

Young people Identified as Being Abusive to Others

Young people of both genders may be identified as being abusive by directing physical, sexual or emotional abuse towards their parents, siblings and/or partner. Young people can be abusive for a number of complex reasons and may have considerable needs themselves. The needs of the young person identified as being abusive to others should be considered separately from those of the person being abused.

A referral should be made to Children’s and Families service in any instance where a young person: aged under 18yrs old:

- Is likely to seriously physically abuse another child or an adult;

- Is likely to seriously emotionally abuse another child or an adult;

- Is likely to sexually abuse another child or an adult; or

- Has already significantly harmed another child or an adult

Please refer to The North Yorkshire Safeguarding Children Partnership Website, Procedures: https://www.safeguardingchildren.co.uk/professionals/nyscb-procedures/

Helping Young People define the difference between Bullying and Domestic Abuse

The definition of bullying that North Yorkshire usually refers to in its work with schools/settings is the one developed by the Anti-bullying Alliance,

“The repetitive, intentional hurting of one person or group by another person or group, where the relationship involves an imbalance of power. It can happen face to face or through cyber space”. [2]

When this is cross-referenced with the definition of domestic abuse, it is easy to begin to draw parallels between areas such as psychological and emotional attack and behaviour that deliberately causes hurt. For a young person it could be very difficult to define the difference between the two. To aid them it is useful if they recognise bullying as an act by a peer/ peer group and domestic abuse as an act by someone they hold an emotional bond with, such as a parent/ guardian or someone they are in a physical or emotional relationship with.

Young People in Same Sex Relationships

A report published by the NSPCC regarding relationship abuse between young people: information for schools provides valuable information that services working with young should be aware of. Abuse in lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) relationships have been identified as being just as common as in heterosexual relationships. A project in Scotland revealed that 52% of respondents had been victims of some form of abusive behaviour from a partner or ex-partner, but only 37% of these victims recognised that the abuse had occurred.

The information pack Another Closet contains the following list of unique aspects of same sex domestic abuse:

- ‘Outing’ as a method of control – the perpetrator may use the threat of ‘outing’ the victim to their friends/family or cultural community if they have not already done so;

- Domestic abuse is not always very well understood in the community – Domestic Abuse may not be as well understood by the LGBT community as most advice and information relates to heterosexual couples. This could lead to the perception that LGBT couples can’t be a victim of domestic abuse;

- Confidentiality and Isolation issues- This is particularly likely in rural communities and in young people’s first same sex relationship. The victim may not feel like there is someone or somewhere safe for them to go. The perpetrator could prevent the victim from seeing community media and turn individuals in the community against them, which is particularly likely if the young person was previously not a familiar member of the community.

Issues Specific to Rural areas

Whilst many of the issues faced by LGBT groups in rural areas may also be faced by heterosexual victims of domestic abuse it is likely, given the facts stated in the previous section, that they would be less aware of available services. As a result young LGBT victims might face the following concerns:

- Support and legal services might be hard to access, as specialist services may not be present and where they are, it may be hard to do so discretely;

- Victims may be physically isolated from friends and family who are part of the LGBT community.

The NSPCC warns that young people who are in LGBT relationships may be at greater risk as they may feel they have to keep their relationships a secret. These young people may be unaware of specialist support available to them from various charity and community groups.

Healthy Relationships

Teenager’s experience at least as much relationship abuse as adults. Several independent studies have shown that 40% of teenagers are in abusive dating relationships, with young women who have older partners and young women from disadvantaged backgrounds at even higher risk.

Domestic abuse is still a ‘hidden’ issue in our society; and it is even more so for teenagers. This is exacerbated by the fact that adolescents can be more accepting of, and dismissive about, this form of behaviour than adults, often justifying their partner’s abusive behaviour.

Young people can have a lack of awareness as to what can be considered a healthy relationship due to a lack of experience and potential susceptibility to gender-role stereotypes. In addition, because of their peer group norms it can be difficult to judge their or their partner’s behaviour objectively.

It is important to note that abuse can happen in any relationship. For some young people entering into same-sex relationships, there may be additional barriers to seeking help, as the young person may not be ready to discuss their sexuality with family and friends and may be unaware of how to access specialist support. Similarly, young men may face additional barriers and fear stigmatisation when reporting abuse in their relationships – particularly with female perpetrators – as a result of dominant ideas of masculinity.

Healthy relationships checklist – IDAS

Red flags and warning signs – IDAS

Domestic Violence Disclosure Scheme (DVDS)

In 2009, Clare Wood was brutally murdered by her ex-boyfriend, who she had met through the internet. He was abusive towards her and she was unaware of his history of violence against women. Her family believed that had they known about his past they may have been able to stop him from killing Clare.

DVDS also referred to as “Clare’s Law”, commenced across England and Wales from 8 March 2014.

The scheme has two functions:

1. Right to Ask – this gives members of the public a formal mechanism to make enquiries about an individual who they are in a relationship with, or who is in a relationship with someone they know, and there is a concern that the person may be violent towards their partner. They have the right to ask the police about that partner’s previous history of domestic violence or violent acts. A precedent for such a scheme exists with the Child Sex Offender Disclosure Scheme.

2. Right to Know – If police checks show that the person has a record of violent offences, or there is other information to indicate a person is at risk, the police will consider sharing this information with the person(s) best placed to protect the potential victim i.e. the police can proactively disclose information in certain circumstances – without the victim asking.

Professionals can refer concerns into the DVDS by contact North Yorkshire Police on the 101 number. The call take will complete the DVDS 1 form which includes details on the perpetrator, person at risk and any connected children. There is now in operation the North Yorkshire Police Single On Line Home. You can now access DVDS via their website. Report a crime | North Yorkshire Police.

Domestic Violence Protection Notice / Orders (DVPN/DVPO):

A Domestic Violence Protection Notice and Order is aimed at perpetrators who present an on-going risk of violence to the victim with the objective of securing a co-ordinated approach across agencies for the protection of victims and the management of perpetrators. The DVPN / DVPO process builds on existing procedures and bridges the current protective gap, providing immediate emergency protection for the victim and allowing them protected space to explore the options available to them and make informed decisions regarding their safety and the safety of their children.

Although the power to issue a DVPN and subsequent application for a DVPO lies with the Police and ultimately the Criminal Justice Service (CJS), the success of any such process will be reliant on the partnership work with other agencies and organisations including those that contribute to Multi-Agency Risk Assessment Conferences (MARACs) and service providers for Independent Domestic Violence Advocates (IDVA’s) Engagement of these agencies with the victim, at the earliest opportunity, is crucial to the success of the DVPN/ DVPO process.

Maximum Sentence for breaching a DVPO is £5000.00 Fine or 2 months imprisonment.

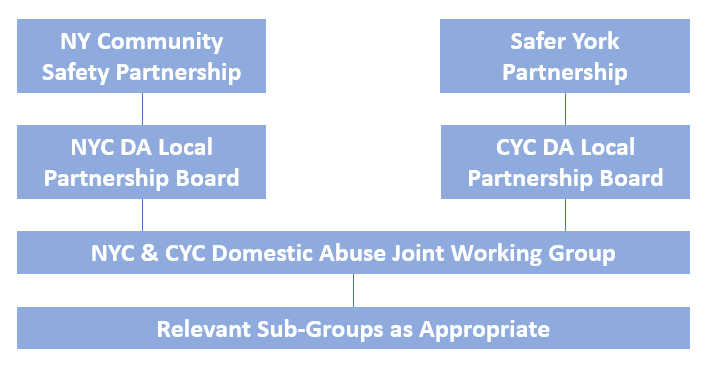

Domestic Abuse Local Partnership Board

The Domestic Abuse Act 2021 Part 4 requires Tier 1 Local Authorities to appoint a Domestic abuse local partnership boards to discharge their duties under the Domestic Abuse Act 2021. This board amongst many others will appoint a person appearing to the authority to represent the interests of children of domestic abuse.

There are two separate Domestic Abuse Local Partnership Boards that represent North Yorkshire and a separate arrangement for the City of York.

The North Yorkshire Domestic Abuse Local Partnership Board will report into the NY Community Safety Partnership Board.

- North Yorkshire Council and City of York Council have joint working groups. Each sub-group provide updates and performance information to separate Community Safety Partnership boards for North Yorkshire and York authorities.

- The flowchart below provides an overview of our governance arrangements:

Multi- agency Risk Assessment Conferencing (MARAC)

Multi Agency Risk Assessment Conferences (MARACs) are recognised nationally as best practice for identifying and managing high risk cases of domestic abuse.

A MARAC is a meeting for agencies to share information about the risk of serious harm or homicide for people experiencing domestic abuse in their area. Multi-agency safety plans are developed to support those most at risk. The aim is to increase the safety and well-being of the adults and children involved, and reduce the likelihood of repeat victimisation. However, only cases identified as ‘high risk’ are discussed at a MARAC.

Where agencies need to respond immediately to ensure the safety of the victim and their children, actions should not be delayed until the case is discussed at the MARAC, and all agencies should refer to their individual agency procedures and North Yorkshire Local Safeguarding Partnership procedures to ensure the protection of victims of domestic abuse and child abuse.

In North Yorkshire and York MARAC Conferences are held virtually using Microsoft Teams and chaired by the North Yorkshire Police Safeguarding Managers/Inspectors. The frequency of meetings are held weekly for the following districts.

Harrogate/Craven

Scarborough/Ryedale

Hambleton/Richmondshire

Selby

York (held twice weekly)

MARAC Referrals:

Any agency can refer a case into a MARAC. Where possible the referring agency should undertake an initial assessment and complete the Risk Indicator Checklist (also referred to as SafeLives, formally CAADA DASH risk assessment) with the victim. The checklist is used by all agencies signed up to the MARAC and establishes a starting point for the risk assessment process

To establish the conclusive level of risk agencies may use the following;

- Professional judgement: if a professional has a serious concern about a victim’s situation, they should refer the case to a MARAC. There will be occasions where the particular context of a case gives rise to serious concerns even if the victim has been unable to disclose the information that might highlight their risk more clearly. This could reflect extreme levels of fear, cultural barriers to disclosure, immigration issues of language barriers, particularly in the case of so-called honour based violence. This judgement would be based on the professional’s experience and/or the victim’s perception of risk

- Visible high risk: 14 ticks in the ‘yes’ boxes

- Potential Escalation: the number of police callouts to the victim as a result of domestic violence in the past 12 months. This can be used to identify cases where there is not a positive indicator of a majority of risk factors on the risk assessment.

Pay particular attention to a practitioner’s professional judgement in all cases. The results from checklist are not definitive assessment of risk. They provide a structure to inform judgement and act as prompts to further questioning, analysis and risk management whether via MARAC or in another way.

A MARAC Referral Form should be completed and sent to the MARAC Coordinator

The referring agency should also provide background information regarding the risk factors and any professional information in support of the referral to ensure full concerns are identified and discussed at the MARAC.

The referral will be identified by the MARAC Coordinator as an ‘initial’ referral if new to the MARAC process, or a ‘repeat’ case, if the victim has been discussed within the past 12 months.

The Case Summary List for each meeting is shared one week in advance of the meeting and provides details for each case to be discussed, allowing agencies to prepare in advance of the meeting. The list includes all referrals received during the previous seven days. It is sent by email to all core MARAC agencies and any other relevant agencies as appropriate to each case.

This will be sent to core attendees of the relevant MARAC seven days prior to the meeting. Other agencies will be invited on a case by case basis as appropriate and will be required to sign a confidentiality agreement.

The referring agency should where appropriate, discuss their concerns with the victim and seek to obtain their consent to share information with other agencies represented on the MARAC.

Perpetrators

Within this guidance we have covered child to parent abuse and the RESPECT programme run by IDAS for those young people displaying abusive behaviours. Covered here will be the key factors and services in place to drive behaviour change of perpetrators in North Yorkshire.

By definition, domestic abuse perpetrators are known to their victims, with most being current or previous intimate partners, but they can also be close or extended family. Although many incidents of domestic abuse are not reported to the police, we know the majority of defendants (92%) in domestic abuse-related prosecutions were men.

We know effective and early risk assessments, combined with the right interventions, can reduce reoffending. We also know that many domestic abusers are repeat offenders.

MATAC – Multi Agency Tasking and Coordination team NYP

This is a multi-agency approach that focuses on identifying serial perpetrators of domestic abuse and is being rolled out in North Yorkshire through the Domestic Abuse: Whole Systems Approach project.

Key aims of MATAC include:

- Preventing further domestic abuse related offending

- Improving victim safety

- Changing offender behaviour

- Improving partnership engagement

THE MATAC RESPONSE –The MATAC response can be summarised as follows:

- The Recency, Frequency and Gravity (RFG) analytical process highlights those perpetrators who cause the most harm.

- Partner agencies may also refer perpetrators into the MATAC process.

- A Multi-agency Tasking and Coordination (MATAC) process actively targets the perpetrators highlighted.

- A domestic abuse toolkit is used to implement a range of tactical options for targeting the perpetrators, including visiting the perpetrators and serving warning and information notices on them.

- Tactics employed include education, prevention, diversion, enforcement and disruption.

- Tactical options include referral to voluntary domestic abuse perpetrator programmes.

Link to MAPPA – MAPPA (Multi Agency Public Protection Arrangements) deals with management of sexual, violent and dangerous persons. This is a statutory process with set criteria for referral. Those individuals already being managed by the MAPPA process will remain there and no further action will be required by the MATAC team. Prior to finalising the MATAC agenda, each perpetrator will be assessed to determine whether they fit the criteria for MAPPA but have not been referred, where this is the case, the designated analyst will liaise with the MATAC coordinator and recommend a MAPPA referral be made. If the MAPPA referral is accepted then the perpetrator will be managed by the MAPPA team. Where the referral is declined, the perpetrator will come back to the MATAC team to be managed.

+Choices Perpetrator Programme – Foundation (behaviour change).

This is a service for perpetrators of domestic abuse, providing an opportunity to recognise, acknowledge and change abusive behaviour. This service is available to everyone regardless of gender or sexual orientation aged 16yrs and over who is a perpetrator of domestic abuse including repeat offenders and adolescents violent toward parents, who wish to voluntarily address their abusive behaviour.

Referral s can be made by agencies working with perpetrators, their families or victims. Explicit consent must be obtained from the individual before a referral can be made.

What +Choices can offer

- Triage and emergency, temporary accommodation for those who do not have access to funds or alternative accommodation.

- One-to-one motivational interventions.

- Tailored Choices Perpetrator Programme, including both one to one and group delivery options.

- Support to address wider needs such as housing, finance, substance misuse and mental health through onward referrals and/or liaison with other support services as appropriate.

Some individuals may require emergency accommodation as they have been removed from their home due to the risks they pose to their victim or family. We will assist in accessing temporary accommodation with support to report to the local housing office the next working day where longer term accommodation is required.

Once a referral is received individuals will be allocated to a project officer and a full needs and risk assessment will be undertaken to identify the most suitable support to address needs.

Individuals ready to engage with the core programme will be supported through a tailored package of interventions to meet their individual needs and guide them through the various stages of the 26 week behaviour change programme.

Referrals can be made using this link to the +Choices page.

Domestic Abuse Coordinators (DAC’s)

There are 4 Domestic Abuse Coordinators working across North Yorkshire and the City of York. Their role primarily is to support the operational functions of Domestic Abuse Officers across various localities for North Yorkshire and York who work with victims and support services to ensure on-going assistance is in place and liaise with front line police officers and supervisors. This will include partnership and multi-agency engagement and development.

The roles of the Domestic Abuse Coordinators are bullet pointed here.

DAC Role

- Line management of DAOs including PDR, Sickness and performance management.

- Management of DA Inbox on Niche – triage of risk for all DA cases, onward referrals to CSC and IDAS at this stage.

- Allocation of DA cases to DAOs, management of workload and tactical advice when required

- Chairing of MARACs if Safeguarding Managers or DA Inspector is unavailable

- Allocation of MARAC research and actions

- Administration of DVDs process – including facilitation of delivery

- DA Matters training – (3 out of 4 DACs are trainers)

- Attendance at Daily management meetings – highlighting cases to action and taking actions for re safeguarding if raised by command

- Delivery of internal training re DA – front office staff, student officers, PCSOs, FCR staff

- Attendance at DA tactical

- Attendance at MAPPA meetings

- Maintenance of DA e mail inbox

- Allocation of work to Stalking team

- Arrange and deliver DA forums

- Deliver external training upon request (army and fire service in last 12 months)

- Dealing with any data breaches that occur to ensure compliance with relevant legislation

The current multi-agency engagement is strengthened further by having one of the four roles primarily focused on partnership development through the delivery of multi-agency forums.

DA Forums

These forums are designed to provide updates to partners on developments locally to nationally around domestic abuse and to share learning from DHR’s and SCR. Partners within these forums will provide updates on practice around domestic abuse which they are delivering or supporting locally.

Scarborough Ryedale forum

Harrogate/Craven forum

Hambleton/Richmondshire forum

York/Selby forum

Forums will be delivered quarterly with agenda setting designed through the DA Tactical meeting and the DA Local Partnership Boards for NYC and CYC.

Barriers to Disclosure

Barriers to disclosure for parents/ carers

Domestic abuse is still largely a hidden crime: those who have experienced abuse from a partner or ex-partner will often try to keep it from families, friends, or authorities

- They may be ashamed of what has happened

- They may feel they were to some extent to blame

- They may love their partner and not want him/her to be criticised or punished for what he did

- They may believe it was a one-off event and won’t happen again

- They may be frightened that if they tell anyone about it, their partner will find out and they will be in danger of further and perhaps more severe abuse from him/her.

- They may fear that their child/ren will be taken into care;

- They may fear death;

- They may believe their abusive partner’s promise that it will not happen again (many partners do not necessarily want to leave the relationship, they just want the violence to stop);

- They may feel that they would have to leave the family home if they disclosed the abuse

For all these reasons, and others, victims of abuse are likely to experience repeated attacks before they report the abuse to anyone – and statistics can only be based on known data. On average, 35 assaults happen before the police are called, and for female victims, women will approach 9 different agencies before they get any effective help.[3]

Safety planning with children and young people

As soon as a professional becomes aware of domestic abuse within a family, if s/he is not a professional working with the family and in a position to provide support they should refer the unborn baby, child to NYC Children and Families using the universal referral form – see https://www.safeguardingchildren.co.uk/about-us/worried-about-a-child/

Safety planning with children and young people means to work with the victim of abuse and each child, according to their age and understanding, to develop a safety plan. If a safety plan already exists, it should be reviewed. This is the role of the relevant professional working with the young person and their family, however if you are concerned about the welfare of the child/young person then a referral to Children and Families should be made.

The plan should emphasise that the best thing a child can do for themselves and their parent/ carer is not to try to intervene but to keep safe and, where appropriate, to get away and contact the police.

The child should be given several telephone numbers, including local police community safety units, local domestic abuse advocacy services, Children and Families, Childline 0800 1111 and NSPCC 0808 800 5000.

When the victim of abuse’s safety plan involves separation from the abusive partner, the disruption and difficulties for the child need to be considered. It must be remembered that, statistically, the victim is at most risk at or around the point of leaving the abusive partner.

Maintaining and strengthening the victim / child relationship is in most cases key to helping the child to survive and recover from the impact of the violence and abuse. Children may need a long term support plan, with the support ranging from mentoring and support to integrate into a new locality and school / nursery school or attend clubs and other leisure / play activities, through to therapeutic services and group work to enable the child to share their experiences & move on from them.

Professionals should ensure that, when planning for the longer term support needs of the unborn baby and/or children at all levels, input is received from the full range of key agencies (e.g. the school, health professionals such as the Midwife, GP & School Nurse, LA housing, an advocacy service, the police community safety unit, Women’s Aid or Refuge, relevant local activity groups and/or therapeutic services).

What to do if you have concerns

Professionals’ responsibilities where a disclosure of domestic abuse is made:

- Offer to speak to the parent/carer or child alone,

- Choose somewhere quiet with no distractions

- Ask open questions

- Take them seriously

- Take and date notes

- Give reassurance and support – they are not alone and you will do whatever you can to stop this happening again

- Explain what services are available

- Explain what you are going to do to help

- Consider safety planning

- Consider safeguarding advice about a referral to Children and families services if a child is at risk of harm

Establish:

- The nature of the domestic abuse

- Children in the home – ages, additional needs etc.

- What the victims immediate fears/risks are

- Somewhere safe to go

- Do they need immediate protection

- Do they need medical attention

Intersectional Approach

An intersectional approach to domestic abuse means services must seek to understand the unique experiences of each family, including their histories, characteristics, and current context, and to see these in the context of unequal societal structures including racism, sexism, and poverty. It requires practitioners to be aware of their own values, biases, and judgements, have safe spaces to reflect, and receive support to separate these from work with families.

Whole Family Approach

A whole-family approach does not separate the abusive behaviours of the parent from the impact on children. It considers the parenting of the abuser, as well as the impact of their abuse on the non-abusing parent and their care for the children. It is important to remember children do not come to services alone: they are part of families. They have relationships with their parents, grandparents and wider networks, as well as with siblings and stepsiblings who they might not live with. Practitioners must gain an understanding of what family means to the children. The full extent of the impact on children of exposure to domestic abuse is often not fully understood until a child feels safe; they will need several opportunities over a period of time to talk about their experiences.

Risk of violence towards professionals should be considered by all agencies who work in the area of domestic violence and abuse and assessments of risk should be undertaken when necessary. It is acknowledged that intimidatory or threatening behaviour towards professionals may inhibit the professional’s ability to work effectively. Effective Supervision and management is important and agencies should take account of the impact or potential impact on professionals in planning their involvement in situations of domestic abuse and make sure they are properly supported.

Being trauma-informed means responding to individuals and families in a non-judgemental, non-blaming and strengths-based way that prioritises building trusting relationships and avoids re-traumatisation. Recognising that people who come to the attention of services have histories, experiences and contexts that are relevant to and impact on their current circumstances.

In relation to those who harm, a trauma-informed approach ensures that the whole person is responded to, but without collusion around their abusive behaviours.

Local Contacts

North Yorkshire Council, Children and Families

T: 0300 131 2 131

E: Social.care@northyorks.gov.uk

W: https://www.northyorks.gov.uk/children-and-families

If abuse is severe or violent then the police should be contacted:

Police:

101, dial 999 in an emergency

Additional support can be gained from:

IDAS: 03000 110 110

Young Minds Parent Helpline: 0808 802 5544

Family Lives Helpline: 0808 800 2222

Services and contacts available

IDAS: 03000 110 110 https://www.idas.org.uk/

Women’s Aid – National charity working to end domestic abuse against women and children. ttps://www.womensaid.org.uk/ helpline@womensaid.org.uk.

Mankind – ManKind support men suffering from domestic abuse from their current or former wife or partner (including same-sex partner). 0182 3334 244 (Monday to Friday, 10am to 4pm) Confidential helpline available for male victims of domestic abuse and male victims of domestic violence across the UK.

Men’s Advice Line – For non-judgemental information and support for male victims of domestic abuse. 0808 8010 327

info@mensadviceline.org.uk Webchat also available.

Hestia – The Respond to Abuse Advice Line is a resource for employers to advise them on how to approach disclosures of domestic abuse by their employees. 07770480437 or 0203 8793695 or email Adviceline.EB@hestia.org between 9am-5pm Monday to Friday for support.

Karma Nirvana – For forced marriage and honour crimes. 0800 5999 247 (Monday to Friday 9am to 5pm).

Young Minds Parent Helpline: 0808 802 5544

Family Lives Helpline: 0808 800 2222

National Stalking Helpline: 0808 2020 300 www.stalkinghelpline.org advice@stalkinghelpline.org

Paladin: Stalking Advocacy Service 0207 8408960

Protection against Stalking (PAS): info@protectionagainststalking.org

www.protectionagainststalking.org

Network for Surviving stalking (NSS): www.nss.org.uk

Stonewall www.youngstonewall.org.uk/

Respect not fear: www.respectnotfear.co.uk/youngpeople/162-young-people-lgbt.html

LGBT Youth: https://www.lgbtyouth.org.uk/domestic-abuse

Think U Know: http://www.thinkuknow.co.uk

For further guidance and information visit the North Yorkshire Safeguarding Children Partnership website at: www.safeguardingchildren.co.uk

[1] Working relationally with couples where there is situational violence

[2] https://www.anti-bullyingalliance.org.uk/tools-information/all-about-bullying/what-bullying

[3] Jaffe, (1982)An integrated response to wife assault: a community model.

Page reviewed: April 2024

View all our news

View all our news